Hepatitis C and Liver Transplants

Hepatitis C and Liver Transplants

Most people know him as the bad guy JR Ewing on the TV show “Dallas.” But lately the actor who played the part, Larry Hagman, has adopted a different role: champion for the cause of organ transplants.

In 1995, Hagman, who had advanced cirrhosis, received a life-saving liver transplant. Since then he has gone on to become honorary chairman of the U.S. Transplant Games, an Olympics-style competition held for patients who have received donated organs. Hagman called the games “a true celebration of a second chance at life for transplant recipients from across the country.”

For patients with advanced hepatitis C liver disease, liver transplants can offer just such a second chance. Cirrhosis of the liver caused by HCV infection is the leading reason for liver transplants. The surgery is complicated and can be risky. Yet it saves lives. About 73 to 77 percent of adult patients survive the operation and resume normal lives. Some 90 percent of liver transplants in children are successful. And new advances in the surgery, including the use of combination anti-viral therapy and “live donor” liver transplants, are improving those odds.

Among those who beat the odds is David Crosby, formerly of the band Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young. Learning from doctors at Johns Hopkins in the 1990s that chronic hepatitis C had “munched” his liver “to a truly amazing degree… so that I had very little function left,” he received a long-awaited liver transplant in 1994. Today, the grateful musician says he is “having a ball” raising a 3-year-old, touring with one of his sons, and making a documentary about musician activism. In his spare time, Crosby has also found time to narrate public service announcements about hepatitis C. “A lot of people think that if they ignore the disease, it will go away,” he told an interviewer recently. “It won’t. It will come knock on your door.”

Who qualifies for transplantation?

Because donated organs are in short supply, doctors carefully screen patients before putting them on the list to receive a liver.

In general, transplants are offered to patients who can’t be treated using drugs or other therapies, and whose disease has become life-threatening. For HCV-infected patients, the most common reason for a transplant is severe cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver. Performing transplants on patients with liver cancer is less common and can be controversial. By the time cancer is detected, it has often spread too far to be cured by a liver transplant.

Transplants are usually not offered to people with ongoing drug or alcohol abuse problems, since the likelihood of success would be small. Crosby, for example, had experimented with needle drugs a few times and developed a serious drinking problem during his years on the road, but had been sober for 10 years before he learned he had hepatitis C. “I had already made the changes that I would recommend to anybody who discovers that they’ve got it, which are: Don’t drink and don’t use,” he told Hep-C Alert. “I had decided that long before, or they wouldn’t have done the treatment.”

Timing is critical for patients who may need a liver transplant. Although transplantation is a last resort, it is important not to wait too long. If a patient’s condition has seriously deteriorated, the chances of a successful liver transplant are lessened. Typically, a team from the liver transplant center determines, in consultation with the patient and family, whether a liver transplant is appropriate. Most centers have medical review boards that assess a patient’s health information and make the final decision.

If a patient is approved, he or she is placed on the national waiting list for liver transplants. The wait can be a long one. It often takes more than a year to find a suitable donor.

Weighing the risks

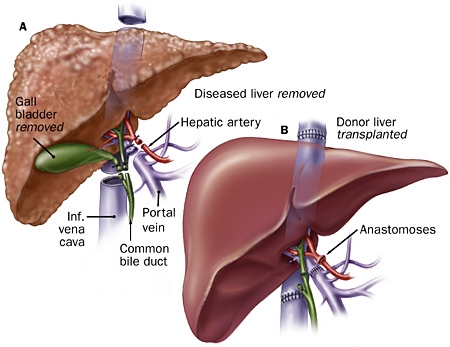

Like all major surgeries, liver transplants carry risks of infection and bleeding. During the surgery, doctors sometimes have difficulty removing the diseased liver. Problems can also arise if the blood vessels connected to the new liver develop clots, reducing blood supply to the transplanted organ. Once the surgery is completed, there is risk that the immune system will reject the organ. This danger can usually be minimized with drugs that suppress the rejection mechanism.

The chances of surviving a liver transplant vary depending on the age and condition of a patient. On average, about three out of four transplant patients survive the first five years after transplantation. Those might not seem like very good odds. But among patients who are in good condition, the survival rate is as high as 90 percent. Among critically ill patients, the survival rate is about 50 percent.

Surgery and recovery

Liver transplants are performed only at major medical centers around the country, by expert teams of transplantation surgeons. In the past, donated organs came only from people who had died and agreed to donate their organs. Recently some centers have also begun performing “live donor” organ transplants, in which part of the liver from a matched donor is removed and transplanted. The surgery is possible because healthy livers can regenerate themselves. Within a year, the part of the liver removed from a donor has fully grown back.

Transplant patients typically spend a few days in an intensive care unit after surgery, where their condition can be carefully monitored. Then they are moved to a regular hospital room for a stay of two to three weeks, on average. Patients who are critically ill at the time of the transplant may need to remain in intensive care and in the hospital longer, up to three months. Once patients leave intensive care, they begin to resume normal diets and are encouraged to get out of bed and walk.

The paradox of rejection

The most dangerous risk for transplantation patients is rejection. This occurs when the body’s immune system attacks and destroys the transplanted organ.

Why does the immune system, which is there to protect us, try to reject the life-saving transplant? Rejection occurs because the immune system’s job is to target and destroy foreign cells that pose a risk. Immune cells identify foreign cells by looking at unique molecular fingerprints on their surfaces and comparing them to the body’s own unique molecular fingerprints.

In this way, the immune system distinguishes between “self” and “non-self.” A donor organ comes from someone whose cells have a different molecular fingerprint. Unfortunately, the immune system reacts as if the body has been invaded.

It unleashes its destructive power to get rid of the foreign cells that it has mistakenly perceived as a threat. If not suppressed, the immune system can destroy a transplanted liver within days.

Several drugs have been developed that stop or slow the rejection process. Anti-rejection drugs may be given by injection during the first several weeks and later in pill form.

All anti-rejection drugs work by suppressing the immune system. As a result, they make patients more susceptible to infections. Other side effects include elevated blood pressure, fluid retention, puffiness, and bone loss. Over time, as the body begins to tolerate the new organ, patients require less anti-rejection medicine.

Still, it’s likely that all transplant patients will have to take the drugs for the rest of their lives. Because of the potentially serious side effects, doctors typically try to lower the dosage to the smallest amount required to prevent rejection. To prevent serious infections, transplant patients are often given antibiotics in pill form.

Liver transplantation doesn’t always succeed. In some cases, the transplanted organ may fail to function. Clots forming in the blood vessels that supply the transplanted organ may cut off blood supply, starving the new liver. Sometimes doctors are unable to stop the rejection process. If the liver begins to fail, a second transplant may be necessary.

For most patients, however, liver transplants are nothing short of a miracle. People who were seriously ill, like Crosby, have been able to return to full, active lives. Some, like snowboarder Chris Klug, compete in the US Transplant Games as a way to inspire other patients facing transplants. In July 2000, Klug received a liver transplant because of a rare congenital liver condition. Five months after the surgery he won a World Cup in the parallel giant slalom. He took home a bronze medal in the 2002 Winter Olympics.

New advances ahead

For HCV-positive patients, a liver transplant doesn’t offer a cure. Because HCV is circulating in the bloodstream, the transplanted liver inevitably becomes infected with the virus. Over time, the infection can begin to injure the new liver.

Fortunately, advances in treating hepatitis C promise to slow that process dramatically. The higher the viral load at the time of surgery, studies have shown, the more quickly symptoms of hepatitis C infection recur in transplant patients.

That finding led scientists to wonder if anti-viral treatments given before surgery could lower viral levels and protect the new liver from damage. To find out, experts at Loyola University Medical Center in Illinois have begun aggressively treating HCV patients with high doses of alpha interferon. Early results suggest that the treatment may help delay recurrence of the disease.

The use of “live donor” liver transplants, meanwhile, could significantly increase the availability of donor organs. Because this technique poses some risk to the healthy donor, however, it remains controversial. In 2002, the National Institutes of Health launched a seven-year study to assess the technique and identify the safest ways to perform the procedure.

Another new advance could help buy time for patients awaiting donor livers. The Mayo Clinic laboratory is developing a bioartificial liver, which operates outside the body like hemodialysis but contains live, functioning liver cells. This new form of therapy is intended not only for patients prior to transplantation but also for those in need of chronic supportive therapy.

— Peter Jaret is a contributing editor for Health magazine and a winner of the American Medical Association’s award for medical reporting. His work has appeared in National Geographic, Newsweek, Hippocrates, and many other national magazines. He is also the author of In Self-Defense (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich), Active Living Every Day, and Heart Healthy for Life.

References

Thomas, R.M. et al., Infection with chronic hepatitis C virus and liver transplantation: a role for interferon therapy before transplantation, Liver Transplantation, September 2003, pg. 905-915

Wiesner, R.H. et al., Recent advances in liver transplantation, Mayo Clinic Proceedings, February 2003, pg. 197-210

The Texas Liver Coalition, www.texasliver.org

HCV Advocate newsletter, An artificial liver device, July 2003

Hep-C Alert Interviews Crosby, www.hep-c.org

US Department of Health and Human Services. Chapter III: Pediatric Transplantation in the United States, 1996-2005. http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/chapter_iii_AR_c…

US Department of Health and Human Services. 2006 OPTN/SRTR Annual Report. http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/chapter_i_AR_cd.htm

Mayo Clinic. Scott L. Nyberg (artificial liver and liver transplantation). http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/nyberg_lab/

Mayo Clinic. Hepatitis C. September 2007. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hepatitis-c/DS00097

American Liver Foundation. Liver Transplant. September 2007. http://www.liverfoundation.org/education/info/transplant/