Fatty Liver Disease

Fatty Liver Disease

Fatty liver disease can range from fatty liver alone (steatosis) to fatty liver associated with inflammation (steatohepatitis). This condition can occur with the use of alcohol (alcohol-related fatty liver) or in the absence of alcohol (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease NAFLD).

Fatty liver disease is now the most common cause for elevated liver function tests in the United States. This is mainly due to the ongoing obesity epidemic in the United States.

Fatty liver can be associated with the use of alcohol. This may occur with as little as 10 oz of alcohol ingested per week. Identical lesions also can be caused by other diseases or toxins.

If steatohepatitis is present but a history of alcohol use is not, the condition is termed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Fatty change in the liver results from excessive accumulation of lipids within hepatocytes. Simple fatty liver is believed to be benign, but NASH can progress tocirrhosis and can be associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. The main risk factors for simple fatty liver (NAFLD) and NASH are obesity, diabetes, and high triglyceride levels.

Pathophysiology

Fatty liver is the accumulation of triglycerides and other fats in the liver cells. In some patients, this may be accompanied by hepatic inflammation and liver cell death (steatohepatitis).

Potential pathophysiological mechanisms include the following: (1) decreased mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation, (2) increased endogenous fatty acid synthesis or enhanced delivery of fatty acids to the liver, and (3) deficient incorporation or export of triglycerides as very low-density lipoprotein.

Frequency

United States

Steatosis affects approximately 25-35% of the general population. Steatohepatitis may be related to alcohol-induced hepatic damage or may be unrelated to alcohol (ie, NASH). NASH has been detected in 1.2-9% of patients undergoing routine liver biopsy. NAFLD is found in over 80% of patients who are obese. Over 50% of patients undergoing bariatric surgery have NASH.

International

Danish and Australian studies show less intense disease progression than studies in the United States. Asian studies reveal NASH and NAFLD at lower body mass indexes (BMIs).1,2,3

Mortality/Morbidity

A natural history study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, revealed that 10% more patients with NAFLD died versus control subjects over a 10-year period. Malignancy and heart disease were the top 2 causes of death. Liver-related disease was the third cause of death (13%), as compared to the 13th cause of death (<1%) for control subjects.

* Steatosis was once believed to be a benign condition, with rare progression to chronic liver disease. Steatohepatitis may progress to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis and may result in liver-related morbidity and mortality.

* Fibrosis or cirrhosis in the liver is present in 15-50% of patients with NASH. Approximately 30% of patients with fibrosis develop cirrhosis after 10 years. Many cases of cryptogenic cirrhosis may represent so-called burnt-out NASH because a high proportion is associated with obesity, type II diabetes, or hyperlipidemia.

* Some patients with drug-induced fatty liver present dramatically with the rapid evolution of hepatic failure. Some patients with inborn errors of metabolism, such as tyrosinemia, may rapidly progress to cirrhosis.

Race

Fatty liver has been found across all races, but most of the research and the highest prevalence appear in the Caucasian race.

A small study evaluating fatty liver disease in the Indian population found its association with the nonobese and its recovery with simple lifestyle habits. However, obesity, when present, was a significant risk factor for NASH in Indians as well as in Koreans.

Interestingly, and as supported in the author’s clinical practice, Asian patients often develop NAFLD and NASH at normal BMIs, but BMIs on the higher range for a patient’s ethnicity. A diagnosis of cirrhosis in an 80-year-old, 5-foot, 110-lb Asian female, with a BMI of 21, is not unusual.Mutations for hemochromatosis appear to put Caucasians at a higher risk of more advanced fibrosis.4

Sex

* As many as 75% of patients in initial reported studies were females.

* In more recent studies, 50% of patients are females.

Age

* Fatty liver occurs in all age groups.

* NAFLD is the most common liver disease among adolescents in the United States. Older age often is predictive of more severe grading of fibrosis.

* NASH is the third most common cause of chronic liver disease in adults in the United States (after hepatitis C and alcohol). It is now probably the leading reason for mild elevations of transaminases.

* NASH has recurred within 6 months after pediatric or adult liver transplant.

Clinical History

* Most patients with fatty liver are asymptomatic. However, if questioned, more than 50% of patients with fatty liver or NASH report persistent fatigue, malaise, or upper abdominal discomfort.

* Symptoms of liver disease, such as ascites, edema, and jaundice, may arise in patients with cirrhosis due to progressive NASH. Laboratory abnormalities during blood donations or life insurance physical examinations often reveal elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and ultimately lead to the diagnosis of fatty liver disease.

Physical

* Hepatomegaly is common.

* Splenomegaly and stigmata of portal hypertension (eg, ascites, edema, spider angiomas, varices, gynecomastia, menstrual disorders) may occur in patients with cirrhosis.

* Patients with drug-induced fatty liver may present with rapid fulminant liver failure.

* In patients who abuse alcohol, extrahepatic effects, such as skeletal muscle wasting, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, or peripheral neuropathy, may be present.

Causes

The most common association with fatty liver disease is metabolic syndrome. This includes carrying the diagnosis of type II diabetes, obesity, and/or hypertriglyceridemia. Other factors, such as drugs (eg, amiodarone, tamoxifen, methotrexate), alcohol, metabolic abnormalities (eg, galactosemia, glycogen storage diseases, homocystinuria, tyrosinemia), nutritional status (eg, overnutrition, severe malnutrition, total parenteral nutrition TPN, starvation diet), or other health problems (eg, celiac sprue, Wilson disease) may contribute to fatty liver disease. There are reports of lean NASH families.

Other Problems to Be Considered

The differential diagnosis is broad. The diagnosis of steatohepatitis requires the exclusion of many factors, including drugs, such as amiodarone, perhexiline maleate, methotrexate, corticosteroids, and estrogens. A diagnosis of NASH can be established only when alcohol excess (>10 g/d) can be excluded. Acute fatty liver can occur during pregnancy and likely results from maternal-fetal interactions related to genetic abnormalities in mitochondrial beta-oxidation of fatty acids.

Workup Laboratory Studies

* No laboratory studies can help definitively establish a diagnosis of fatty liver or NASH.

* Aminotransferases

* The only abnormality may be an elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or ALT level. These levels may be elevated as much as 10-fold. However, the AST and ALT levels may be normal in some patients with fatty liver or NASH.

* In the absence of cirrhosis, an AST-to-ALT ratio of greater than 2 suggests alcohol use, whereas a ratio of less than 1 may occur in patients with NASH.

* Alkaline phosphatase

* This level can be elevated in some patients with NASH.

* Usually, it is less than 2- to 3-times normal.

* Lipids

* Hyperlipidemia may be present.

* Increased triglycerides are common in children and in patients with metabolic syndrome.

* Iron studies

* Elevations in serum ferritin, iron, and/or decreased transferrin saturation may occur in patients with NASH.

* Although iron overload occurs in a small proportion of patients with NASH, these patients have more severe disease. An iron index score may be ordered on a liver biopsy specimen to evaluate for phlebotomy. Hemochromatosis gene testing is recommended when the ferritin is significantly elevated. Simply eliminating dietary iron has been shown to improve fatty liver.

* Viral serological markers: Before a diagnosis of NASH can be made, viral markers should be tested and viral infection excluded.

* Autoimmune markers, such as antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti–smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), are often slightly elevated in NASH.

* Positive antibodies are associated with more severe fibrosis levels.

* In the appropriate clinical setting, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and anti–liver-kidney antibody may lead to a diagnosis of autoimmune liver disease.

* Fasting insulin and glucose levels will alert the clinician to potential glucose intolerance and may lead to more effective therapies.

Imaging Studies

* Ultrasound

* The liver is hyperechogenic or bright.

* Steatosis is detected only when substantial (30% or more) fatty change is present.

* Studies in patients who are about to undergo gastric bypass surgery reveal a 93% predictive value of NASH, with an accuracy of 76%.

* Computed tomography

* The mean CT (Hounsfield unit) number is lower in the liver than in the spleen.

* CT scans may be used to monitor the course of the disease on successive scans.

* Focal fatty lesions may be identified by dual-energy CT scans that demonstrate increased attenuation with increasing energy and no change in normals.

* Magnetic resonance imaging

* MRI may be useful for excluding fatty infiltration. Phase-contrast imaging correlates with the quantitative assessment of fatty infiltration across the entire range of liver disease.

* Loss of intensity on T1-weighted images may be useful in identifying focal fat.

* Noninvasive studies, such as ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI, may identify the presence of a fatty liver. However, these imaging techniques cannot distinguish between benign steatosis and steatohepatitis. Benign steatosis may be focal or diffuse, whereas steatohepatitis is usually diffuse.

Other Tests

* Because fatty liver is common in the Western world and since NASH carries a 10% risk of cirrhosis, a simple blood test predictive of which patients would have worse disease is desirable. This has led to studies of databases, rat models, scoring systems, prospective studies, and novel uses for old markers of inflammation and scarring.2,8,9,10,11

* The easily obtained NAFLD fibrosis score that consists of age, hyperglycemia, BMI, platelet count, albumin and AST/ALT ratio appears easy to use and promising to avoid excessive liver biopsies.12

* Another promising tool has been reported. Kotronen et al developed a method for predicting NAFLD based on routinely available clinical and laboratory data.13 Analysis of 470 subjects in whom liver fat content was measured with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed independent predictors of NAFLD were the presence of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, fasting serum insulin, fasting serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and the AST/alanine aminotransferase ratio13 . Validation of the score demonstrated an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.86. The optimal cut-off point of -0.640 predicted increased liver fat content with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 71%.

* Other noninvasive commercial tests for fibrosis (eg, FIBROSpect, FibroSURE, FibroScan) have not yet been proven in the Western population for NASH; however, large studies are ongoing.

Procedures

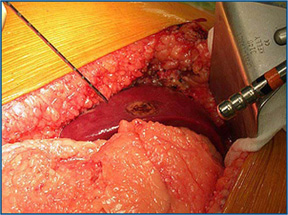

* Liver biopsy

* A liver biopsy and histopathologic examination are required to establish the diagnosis.

* The diagnosis should be considered in all patients with unexplained elevations in serum aminotransferases (eg, with findings negative for viral markers or autoantibodies or with no history of alcohol use).

* The Brunt classification is the standard used to report NAFLD and NASH biopsy specimens.14

Histologic Findings

The diagnosis of fatty liver or NASH can be established only with a liver biopsy. Specific histologic findings include the following: (1) steatosis, which usually is macrovesicular but may be microvesicular or mixed; (2) inflammatory infiltrates consist of mixed neutrophilic and mononuclear cells, and portal infiltrates usually are not seen (unlike in hepatitis C); (3) ballooning degeneration; and (4) fibrosis. The first 3 findings are used to calculate the NAFLD activity score (0-8).

Staging

The stage of disease is determined by the NAFLD activity score and the amount of fibrosis.

Treatment

Medical Care

Abstinence from alcohol may reverse steatosis in patients with alcohol-related fatty liver. Weight loss and control of comorbidities appear to slow the disease and to possibly reverse some of the steatosis and fibrosis. No established treatment is available for NASH. Several empiric treatment strategies have been suggested, as outlined below.

* Treatment of underlying disease

* Patients with celiac sprue who follow a gluten-free diet can have reversal of fatty liver disease.

* Patients with growth hormone deficiency who receive growth hormone can have reversal of NASH.15

* Dieting

* Diets associated with improvement include those restricted in rapidly absorbed carbohydrates and those with a high protein-to-calorie ratio. Weight loss should be gradual, moderate, and controlled.16

* Exercise added to diet appears to improve results and to increase insulin sensitivity by increasing muscle mass.

* Surgical Care

* Bariatric surgery

* Several studies are emerging that indicate that bariatric surgery with appropriate weight loss results in both chemical improvement and histologic improvement of NASH.42

* Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with repeat biopsy within 2 years has shown improvement in 100% of patients. One study showed 94% of repeat liver biopsies no longer met the pathologic criteria for NAFLD or NASH. Another study, which only rebiopsied livers of patients with NASH (not NAFLD), demonstrated that 89% no longer had NASH.43,44,45,46

* Early studies reporting possible worsening hepatic function after rapid weight loss have not been substantiated. This may be a viable option in the appropriate candidate.

Consultations

The only way to firmly diagnosis NASH is with a liver biopsy. Often, a clinical picture of obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated transaminases is enough to conclude that a patient has NASH. However, underlying alcohol or other drug ingestion as well as smoldering autoimmune or hemochromatosis must be ruled out. Referral to a hepatologist with or without liver biopsy may help in staging and prognosis.

Diet

* Abstinence from alcohol may reverse steatosis in patients with alcohol-related fatty liver.

* A low-fat, American Diabetes Association (ADA) diet is recommended.

* A weight loss goal of 1-2 pounds per week is recommended.

Activity

Exercise that includes both cardiovascular fitness and weight training should improve NASH. Cardiovascular fitness often results in weight loss. Weight training will increase muscle mass and improve insulin sensitivity. Both of these activities together help relieve the underlying derangements of NASH. However, no randomized trials with weight-bearing exercise have been published to date.

Medication

No proven medical therapy is available.

Follow-up

Further Outpatient Care

* All patients with chronic liver disease should be tested for hepatitis A total antibodies and vaccinated if needed. Physicians should also consider testing for hepatitis B surface antibody and vaccinating in the appropriate clinical situation (ie, life expectancy, >20 y).