Challenging Old Assumptions About Alcoholism

Old Assumptions

By MARTIN DOWNS

Dr. Mark L. Willenbring is the director of the Treatment and Recovery Research Division at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. As a researcher, he focuses on developing and implementing evidence-based guidelines for treating addiction. He is also a practicing addiction psychiatrist and a distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. Before joining the alcohol institute in 2004, he was a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine and medical director of the Addictive Disorders Section at the Veteran’s Affairs Medical Center in Minneapolis.

Q. Have there been major changes recently in the way alcoholism is treated?

A. One of the shifts that’s taking place is moving away from focusing only on extreme forms of heavy drinking, especially people in treatment programs, which are the extreme of the extreme. These are the people that everybody thinks about when they think, well, who’s an alcoholic? What does an alcoholic look like? O.K., well, they lose their jobs; they lose their families; they’re multiple D.W.I. offenders; they are in and out of hospitals; they’re skid row drunks; waking up in the morning, they can’t remember the night before. That’s the stereotype.

Most of the people who develop dependence are functional. They don’t actually get very disabled from this. It turns out that a problem on the job, a serious problem with your family, serious problems with your health — these kinds of things only occur at the very late stages. Most people who develop dependence — that is, they can’t reliably control their drinking — are functional. They’re employed; they have health insurance; they have stable family lives; they go to church on Sunday. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t suffering. We need to make treatment very widely available for people with mild to moderate dependence, and currently they’re not getting treated at all.

Q. Do these people with milder dependence eventually become more extreme alcoholics?

A. There are some really astonishing new findings. One is that over 70 percent of people who develop an episode of alcohol dependence in their lifetime have a single episode that lasts on average three or four years, and then they remit and they don’t relapse. About 12 percent of adults have had alcohol dependence in their lifetime, at some point.

This is from this new study called the National Epidemiological Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. It is the largest psychiatric epidemiological study ever done; 43,000 people were interviewed. This is a household probability sample of the United States population, and what makes it absolutely unique is that the same people were interviewed three years later. So we have all this new information about the natural history, about relapse, about incidence and about subtypes.

Most of what we previously knew about alcoholism has been based on studies of 40-year-old white male alcoholics in treatment. Almost everything we hear about the disorder is based on that very small population.

Q. That’s basically the profile of Bill W., the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, right?

A. Precisely. It’s the profile of A.A.; it’s the profile of treatment program participants. These are people that have been ill for decades. They almost all have the chronic relapsing form. Most of them have coexisting psychiatric disorders. A lot of them have other things like social disability or physical disorders. It’s a pretty ill bunch.

If you look back over the history of how we learn about diseases, it always starts with the hospitalized people, and then over time gets to milder sorts of outpatient groups. Then when you get to the community, you get the full view, and that’s what we’re getting now. We’re finally understanding what the spectrum of the disorder actually looks like. And we’re finding it’s not this either/or thing.

About one-third of those who develop dependence do so at about age 19 to 20. For the most part, they have a relatively mild form, and almost all get well eventually. By age 25 most of them have resolved.

About 40 percent of alcoholics have midlife onset, typically in their mid-30s. They have a relatively mild to moderate form, on average. They’re more likely to have a family history of alcohol dependence or psychiatric disorders like depression and anxiety. This is the more common pattern among women. Few of them seek any kind of help, even like talking to their minister or their doctor or psychologist. Almost none of them end up in a treatment program at this point.

And then you have the other 30 percent who have a very early onset of dependence, in their midteens. Most of them have a family history, and it’s much more common among men, and they’re much more likely to have antisocial traits. They’re the ones who are most likely to develop the relapsing form of alcoholism and end up in treatment programs.

Q. Does this mean that a 12-step program may not be the best treatment for all alcoholics?

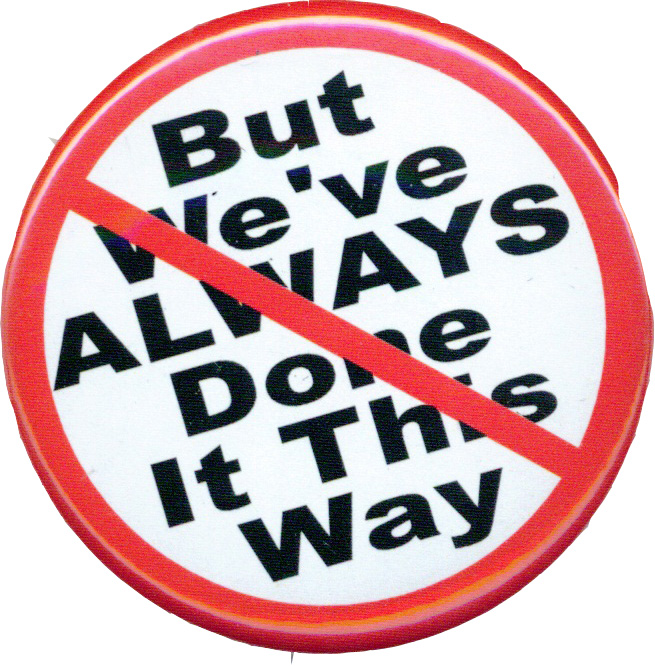

A. It’s a tool in our toolbox, but for the past 40 years it’s been the only tool. Unfortunately, even though we have many more tools available, they’re not being used. More than 90 percent of treatment programs in the country right now provide only group counseling and A.A.

Even though we have medications that are efficacious, they’re not being used. People aren’t even being told about them. This is all about using every tool at our disposal. It’s not about A.A. or medication. I treat patients who are taking medications, and I’ll always encourage them to go to A.A., and many are — there’s no incompatibility.

In terms of behavioral treatments, one of the prominent behavioral researchers in this field once said, “I think the glass is half full — if we only had a glass.” We don’t currently have a vehicle for implementing innovative treatments.

Q. How do you think treatment could be approached differently?

A. The only way I think we can make treatment accessible to the vast majority of people — again, who are functional and who have health insurance — is to use the health care system.

At this point, in any given year, maybe 5 percent of people with alcohol dependence actually go to a rehab program. If the other 95 percent of people with alcohol dependence all showed up at the treatment center door, we wouldn’t have capacity. Not only that, but my belief is that for most people that is not a very appealing form of treatment. It’s often difficult to access; it’s very inconvenient, and I think most Americans frankly don’t like therapy much, let alone group therapy. And then finally when you enter a treatment program, you really are labeled with a stigmatizing diagnosis in a very unspecific way. I think it’s similar to being hospitalized for treatment of depression.

The spectrum is very much like it is for depression. Where we are right now with alcohol dependence is where we were with depression 35 years ago. So we want to move the model for treating alcohol dependence much more toward the way depression is currently treated. And I think that’s going to happen. Pieces of the puzzle are gradually being put in place.

What’s probably going to change it is the right medication. I think what we’re moving to for most of these functional, moderately ill folks is similar to what we do with functional, moderately ill depressives. I think most of them will be treated with a medication and some brief counseling.

Q. It sounds like this fits with the renewed emphasis on primary care in the American health system. Do you think that family doctors should be treating alcoholism?

A. That’s exactly what we’re talking about here — dealing with at-risk drinking and with mild to moderate alcohol dependence in the context of primary care. We now have disease management programs that have been proven to be effective. This is a disorder that’s going to be treated like asthma or like depression or like hypertension.

I think the other place that often gets neglected is psychiatric care. A lot of people see psychiatrists, but psychiatrists don’t do any better than other doctors at addressing alcohol use. So that’s a big focus for us as well. It’s really equal with primary care.