Esophageal Varices

Esophageal Varices

The portal vein carries approximately 1500 mL/min of blood from the small and large bowel, the spleen, and the stomach to the liver. Obstruction of portal venous flow, whatever the etiology, results in a rise in portal venous pressure. The response to increased venous pressure is the development of a collateral circulation diverting the obstructed blood flow to the systemic veins. These portosystemic collaterals form by the opening and dilatation of preexisting vascular channels connecting the portal venous system and the superior and inferior vena cava.1,2,3

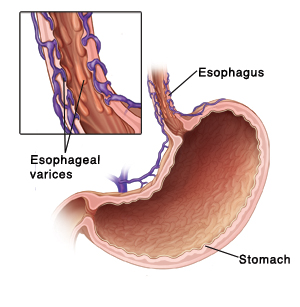

High portal pressure is the main cause of the development of portosystemic collaterals; however, other factors such as active angiogenesis may also be involved. The most important portosystemic anastomoses are the gastroesophageal collaterals. Draining into the azygos vein, these collaterals include esophageal varices, which are responsible for the main complication of portal hypertension — massive upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage.

The most common causes of upper GI bleeding are duodenal (35%) and gastric ulcers (20%). Bleeding from esophageal varices is responsible for only 5-11% upper GI bleeding (incidence varies depending on geographic location). Other causes for upper GI bleeding are acute gastric erosions/hemorrhagic gastritis (18%), Mallory-Weiss tears (10%), gastric carcinoma (6%), and other causes (6%).

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine’s Esophagus, Stomach, and Intestine Center, Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas Center, and Heartburn/GERD/Reflux Center. Also, see eMedicine’s patient education articles Gastrointestinal Bleeding, Cirrhosis, and Gastritis.

Pathophysiology

Obstruction of the portal venous system at any level leads to increased portal pressure. Normal pressure in the portal vein is 5-10 mm Hg because the vascular resistance in the hepatic sinusoids is low. An elevated portal venous pressure (>10 mm Hg) distends the veins proximal to the site of the block and increases capillary pressure in organs drained by the obstructed veins.

Because the portal venous system lacks valves, resistance at any level between the right side of the heart and the splanchnic vessels results in retrograde flow of blood and transmission of elevated pressure. The anastomoses connecting the portal and systemic circulation may enlarge to allow blood to bypass the obstruction and pass directly into the systemic circulation.

Studies have demonstrated the role of endothelin-1 (ET-1) and nitric oxide (NO) in the pathogenesis of portal hypertension and esophageal varices.2,4 ET-1 is a powerful vasoconstrictor synthesized by sinusoidal endothelial cells that has been implicated in the increased hepatic vascular resistance of cirrhosis and in the development of liver fibrosis. NO is a vasodilator substance that is synthesized by sinusoidal endothelial cells. In the cirrhotic liver, the production of NO is decreased, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and nitrite production by sinusoidal endothelial cells are reduced.

Obstruction and increased resistance can occur at 3 levels in relation to hepatic sinusoids, as follows:

Presinusoidal venous block (eg, portal vein thrombosis, schistosomiasis, primary biliary cirrhosis): These lesions are characterized by elevated portal venous pressure but a normal wedged hepatic venous pressure (WHVP).

Postsinusoidal obstruction (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, venoocclusive disease, in which the central hepatic venules are the primary site of injury): WHVP is characteristically elevated.

Sinusoidal obstruction (eg, cirrhosis) is characterized by increased hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), with WHVP being equal to portal venous pressure.

Gastroesophageal varices have 2 main inflows, the first is the left gastric or coronary vein. The other major route of inflow is the splenic hilus, through the short gastric veins. The gastroesophageal varices are important because of their propensity to bleed.

Studies of hepatic microcirculation have identified several mechanisms that may explain the increased intrahepatic vascular resistance. These mechanisms may be summarized as follows:

A reduction of sinusoidal caliber due to hepatocyte enlargement

An alteration in the elastic properties of the sinusoidal wall due to collagen deposition in the space of Disse

Compression of hepatic venules by regeneration nodules

Central vein lesions caused by perivenous fibrosis

Venoocclusive changes

Perisinusoidal block by portal inflammation, portal fibrosis, and piecemeal necrosis

The following are risk factors for variceal hemorrhage:

Variceal size: The larger the varix, the higher the risk of rupture and bleeding. However, patients may bleed from small varices too.

The presence of endoscopic red color signs (eg, red whale markings, cherry red spots)

The Child classification, especially the presence of ascites, increases the risk of hemorrhage.

Active alcohol intake in patients with chronic alcohol-related liver diseases

Local changes in the distal esophagus (eg, gastroesophageal reflux) have been postulated to increase the risk of variceal hemorrhage. However, evidence to support this view is weak. Studies indicate that gastroesophageal reflux does not initiate or play a role in esophageal hemorrhage.

A well-documented association exists between variceal hemorrhage and bacterial infections, and this may represent a causal relationship. Infection could trigger variceal bleeding by a number of mechanisms, including the following:

The release of endotoxin into the systemic circulation

Worsening of hemostasis

Vasoconstriction induced by contraction of stellate cells

Frequency

United States

In Western countries, alcoholic and viral cirrhosis are the leading causes of portal hypertension and esophageal varices.Thirty percent of patients with compensated cirrhosis and 60-70% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis have gastroesophageal varices at presentation.

The de novo rate of development of esophageal varices in patients with chronic liver diseases is approximately 8% per year for the first 2 years and 30% by the sixth year.

The risk of bleeding from esophageal varices is 30% in the first year after identification.

Bleeding from esophageal varices accounts for approximately 10% of episodes of upper GI bleeding.

International

Hepatitis B is endemic in the Far East and Southeast Asia, particularly, as well as South America, North Africa, Egypt, and other countries in the Middle East. Schistosomiasis is an important cause of portal hypertension in Egypt, Sudan, and other African countries. Hepatitis C is becoming a major cause of liver cirrhosis worldwide.

Mortality/Morbidity

Patients who have bled once from esophageal varices have a 70% chance of rebleeding, and approximately one third of further bleeding episodes are fatal. The risk of death is maximal during the first few days after the bleeding episode and decreases slowly over the first 6 weeks. Mortality rates in the setting of surgical intervention for acute variceal bleeding are high.

Associated abnormalities in the renal, pulmonary, cardiovascular, and immune systems in patients with esophageal varices contribute to 20-65% of mortality.

Sex

In females with esophageal varices, alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, venoocclusive disease, and primary biliary cirrhosis are usually responsible.

In males with esophageal varices, alcoholic liver disease and viral hepatitis are usually responsible.

Age

Portal vein thrombosis and secondary biliary cirrhosis are the most common causes of esophageal varices in children.

Cirrhosis is the most common cause of esophageal varices in adults.

Clinical History

Symptoms of liver disease

Weakness, tiredness, and malaise

Anorexia

Sudden and massive bleeding with shock on presentation

Nausea and vomiting

Weight loss – Common with acute and chronic liver disease, mainly due to anorexia and reduced food intake, and regularly accompanies end-stage liver disease, when a loss of muscle mass and adipose tissue is often a striking feature

Abdominal discomfort and pain – Usually felt in the right hypochondrium or under the right lower ribs (front, side, or back) and in the epigastrium or the left hypochondrium

Jaundice or dark urine

Edema and abdominal swelling

Pruritus – Usually associated with cholestatic conditions, such as extrahepatic biliary obstruction, primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing cholangitis, cholestasis of pregnancy, and benign recurrent cholestasis

Spontaneous bleeding and easy bruising

Encephalopathic symptoms – Disturbance of the sleep-wake cycle, deterioration in intellectual function, memory loss and, finally, inability to communicate effectively at any level, personality changes, and, possibly, display of inappropriate or bizarre behavior

Impotence and sexual dysfunction

Muscle cramps – Common in patients with cirrhosis

Past medical history

Previous jaundice suggests the possibility of a previous acute hepatitis, hepatobiliary disorder, or drug-induced liver disease.

Recurrence of jaundice suggests the possibility of reactivation, infection with another virus, or the onset of hepatic decompensation.

Patients may have a history of blood transfusion or administration of various blood products.

A history of schistosomiasis in childhood may be obtained from patients in whom infection is endemic.

Intravenous drug abuse

Family history of hereditary liver disease such as Wilson disease

Lifestyle and history of diseases, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia

Risk factors for upper GI bleeding

Bleeding diathesis

Peptic ulcer disease

Use of alcohol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Documented cirrhosis

Documented episodes of GI tract bleeding

History of recent vigorous retching or emesis before an attack of hematemesis or melena

Physical

Pallor may suggest active internal bleeding.

Low blood pressure, increased pulse rate, and postural drop of blood pressure may suggest blood loss.

Parotid enlargement may be related to alcohol abuse and/or malnutrition.

Cyanosis of the tongue, lips, and peripheries due to low oxygen saturation may be observed.

Patients may experience dyspnea and tachypnea.

A hyperdynamic circulation with flow murmur over the pericardium may be present.

Jaundice may be present because of impairment of liver function.

Look for telangiectasis of the skin, lips, and digits.

Gynecomastia in males results from failure of the liver to metabolize estrogen, resulting in a sex hormone imbalance.

Fetor hepaticus occurs in portosystemic encephalopathy of any cause (eg, cirrhosis).

Palmar erythema and leuconychia may be present in patients with cirrhosis.

Ascites, abdominal distention due to accumulation of fluid, may be present. Ascites may be associated with peripheral edema and may involve the abdominal wall and genitalia.

Numerous dilated veins radiating out of the umbilicus may be observed. Distended abdominal wall veins may be present, with the direction of venous flow away from the umbilicus.

The liver may be small.

Splenomegaly occurs in portal hypertension.

Testicular atrophy is common in males with cirrhosis, particularly those with alcoholic liver disease or hemachromatosis.

Venous hums, continuous noises audible in patients with portal hypertension, may be present as a result of rapid turbulent flow in collateral veins.

During the rectal examination, obtain a stool sample for visual inspection. A black, soft, tarry stool on the gloved examining finger suggests upper GI bleeding.

Causes

Diseases that interfere with portal blood flow can result in portal hypertension and the formation of esophageal varices. Causes of portal hypertension usually are classified as prehepatic, intrahepatic, and posthepatic.

Prehepatic

Splenic vein thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis

Extrinsic compression of the portal vein

Intrahepatic

Congenital hepatic fibrosis

Hepatic peliosis

Idiopathic portal hypertension

Sclerosing cholangitis

Tuberculosis

Schistosomiasis

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Alcoholic cirrhosis

Hepatitis B virus–related and hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis

Wilson disease

Hemachromatosis

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Chronic active hepatitis

Fulminant hepatitis

Posthepatic

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Thrombosis of the inferior vena cava

Constrictive pericarditis

Venoocclusive disease of the liver